But the Daily Office or Liturgy of the Hours (Morning and Evening Prayer, for most Anglicans) has itself a rich and varied tradition, and its celebration can take varied forms. Liturgists have often used a two-fold schema to describe the diversity of ancient and medieval daily prayer, dividing instances into "Cathedral" and "Monastic". These are ideal types to help us understand real acts of communal prayer, not rigid categories - but they clarify how different daily prayer can be, while at the same time revealing a core of actions more specific than (or just plain different to) what often passes for "worship". This discussion of the two ways owes something to Paul Bradshaw's accessible work of the same name.

But the Daily Office or Liturgy of the Hours (Morning and Evening Prayer, for most Anglicans) has itself a rich and varied tradition, and its celebration can take varied forms. Liturgists have often used a two-fold schema to describe the diversity of ancient and medieval daily prayer, dividing instances into "Cathedral" and "Monastic". These are ideal types to help us understand real acts of communal prayer, not rigid categories - but they clarify how different daily prayer can be, while at the same time revealing a core of actions more specific than (or just plain different to) what often passes for "worship". This discussion of the two ways owes something to Paul Bradshaw's accessible work of the same name.Two ancient texts help exemplify the two ways of praying. The first is from John Cassian, monastic researcher and founder, who shares an account of the Egyptian desert monks praying as a group:

…when the Psalm is ended they do not rush to bend the knee, as some of do in this region… but before they bend their knees they pray briefly, and standing spend a longer time in prayer. So after this, they prostrate themselves on the ground for a moment, as though worshipping such divine mercy, then rise together promptly again and, upright with outstretched hands, pray standing as before while remaining intent upon their petitions…. But when the one who is going to collect the prayer has risen from the ground get up similarly, so that no one would presume to bend the knee before he bows, nor to remain when he has risen from the ground, in case he is thought to have celebrated his own prayer instead of following the leader to the conclusion (Institutes 2.7).This is a group praying simply and without regard to particular objects or spaces, and with hardly any differentiation of persons and roles. One "collects" the prayer, but clergy are not mentioned. It is as though this group is sharing private and personal prayer in a communal setting. This is the "monastic" way of praying, meditative, thorough, and profoundly biblical; its descendants are, predictably enough, found in convents and cloisters even today.

The second is from a similar time but could hardly be more different - the pilgrim Egeria, also researching liturgy and life in the East, describes daily prayer in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem:

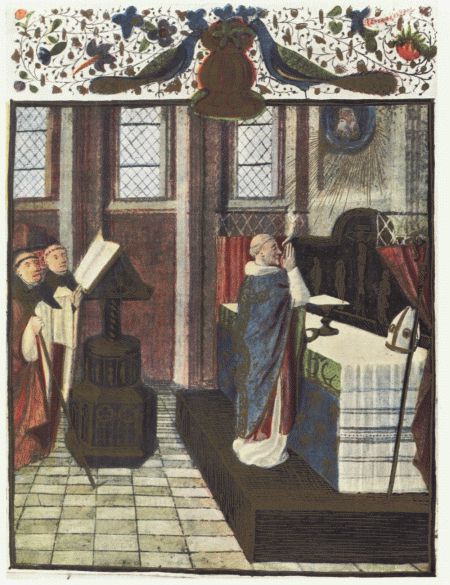

Every day before cockcrow all the doors of the Anastasis are opened, and all the monks and virgins as they call them here, and not they alone but lay people as well, men and women, who desire to keep a vigil early go there. And from that hour until it is light hymns and psalms are sung responsively and antiphons similarly; and prayer is made after each of the hymns. For presbyters in twos or threes, and similarly deacons, and monks take it in turn every day with the monks to say prayers after each of the hymns or antiphons. But when day breaks they begin to say the morning hymns. Then the bishop arrives with the clergy, and immediately enters into the cave, and from within the rails he first says a prayer for all; he commemorates those names he wishes; he then blesses the catechumens. Then he says a prayer and blesses the faithful. And after this as the bishop is going out from within the rails, everyone approaches his hand, and he blesses them one by one as he goes out, and thus the dismissal takes place by daylight (Itinerary of Egeria 24.1-2).Here there seems to be color and movement, actions and objects aplenty; where Cassian's monks were quietly adoring, the inhabitants Jerusalem are praising noisily. This is the "Cathedral" form of prayer, an activity that joins in and sanctifies the bustle of daily life. Its descendants are not only the "solemn" forms of Daily Office accompanied by processions or incense etc., but perhaps also many other non-eucharistic forms of communal prayer and praise (however unwitting the participants are of the connection).

There are other differences, less apparent from these quotes alone. The monks seem to have worked their way through the whole Psalter, and quite often at that; the Jerusalemites seem to have used just a few Psalms repeatedly. The latter was complex as an event in form, but simpler in its content. But the centrality of the Psalms is common to them, and not to be overlooked. If there is a single characteristic of Christian daily prayer across the centuries, that anchors us in catholicity and helps us avoid self-focussed feeding of our own prejudices and preferences, it is the use of the Psalms.

Two conclusions suggest themselves: first, it is possible to celebrate the Daily Office in quite different ways and still be in close connection with a great tradition of prayer; second, the Psalms - not singing in general, or even the Bible in general - are as close as we might come to a persistent core of daily prayer. Practically speaking, this means we might have great scope to vary the specific forms and moods of daily prayer, but if we do not have a sense of what we are doing or why, we are likely to flounder liturgically.

And if the Psalms are not central, or even present, then we are not doing what the Church has characteristically done across its centuries of daily prayer, becoming what Augustine called the totus Christus - the body of Christ, praying with and to its head.