Historically most churches are oriented to the East, i.e., the holy table or altar stands in the east end, typically in a chancel or apse, with the body or nave of the church to its West. Those present for the Holy Communion or for Morning and Evening Prayer are thus facing the East to pray, which is an ancient and widespread custom reflecting faith in the Resurrection.

This is not a universal pattern, however. Some of the earliest Christian Churches were oriented the opposite way; the most famous is St Peter's in Rome, which faces West rather than East . However by the time the Old St Peter's was built in the 4th century, prayer to the East was a Christian norm; so when the Eucharist was celebrated there, originally priest and people faced East - towards the main doors, not away from them - during the Great Thanksgiving. Architectural orientation was therefore less important than physical or personal orientation. It was possible and even likely that the priest would face east, with the people, but not in the East of the church.

Churches in Roman Africa, which unlike those in Europe were ruined rather than remodeled, reveal something similar. Although these ancient churches were often oriented to the East like more recent ones, slots where the marble panels of chancel screens were inserted are visible on the floors of basilicas, not in the East but in the middle, far from the apse where the clergy sat. While an enclosure was created for the (portable) altar, the people gathered around it with the priest, and prayed with him towards the East.

In the Medieval West however, architectural and geographical orientation became more closely tied as the altars migrated to the East end of churches with few exceptions. This was the situation at the time of the English Reformation.

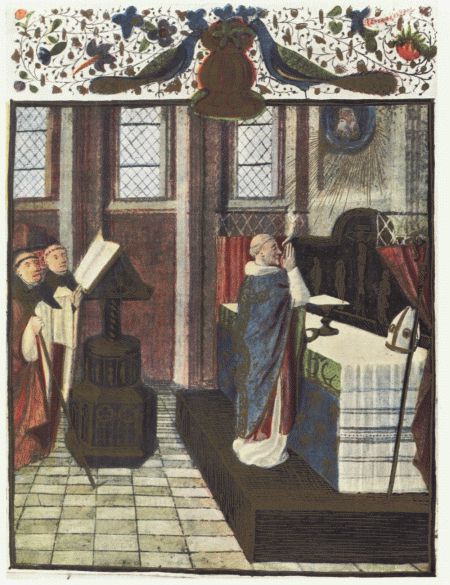

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer retains the instruction from its 1552 predecessor that the priest stand on the North side of a table in the body of the church (or in the chancel). It was intended that the altar again become more of a table with the communicants gathered around it; the East was not intended to be a particular focus. However altars had been returned to the East end of English churches before 1662, making this an odd or redundant instruction; and most Anglican priests continued to face East (ad Orientem) with the people, but at some distance from them, in the East end of the church.

In recent centuries, urban spaces have sometimes made geographical eastward orientation impossible when constructing new church buildings; but the liturgical orientation had become fixed to the architecture of the church, rather than floating free from it as in ancient times so as to recognize the actual East. Thus churches might be built of necessity with an "East" that wasn't East at all, but was the direction for prayer simply because it was the direction of chancel and altar in a long narrow space. Melbourne Anglicans may be aware that their St Paul's Cathedral is actually oriented North-South, although a fictive "liturgical" East and West are often mentioned.

Liturgical reform across Christian churches in the twentieth century however saw altars moved away from East walls to allow the priest to face the people (versus populum). This has become normal, but is not well understood, or even generally well practiced.

This move changes the relationship between architectural and human orientation yet again, creating a focus not in the East (either literal or liturgical) but within the assembly, or on the altar itself. The implied sense of space of this practice is more that of a circle with a focus, than of a line pointing outwards to transcendent infinity.

Unfortunately however the implementation of this change has usually been a compromise that balked at the real implications of the intended change, or was simply defeated by the stolidly longitudinal forms of existing buildings. Pulling a distant altar away from an East wall to leave room for a priest behind it creates not a gathered community but a more-distant priest. To add another table just a few meters further along a chancel is visually confusing at best.

So rather than allowing either the traditional emphasis on transcendence or the new focus on immanence to speak clearly, the versus populum arrangement often creates a sort of axis between clergy on the one hand and people on the other.

Odd as it may seem, versus populum can often be more clericalist than the old way; it emphasizes the personality of the priest (sometimes in highly problematic ways) and can make him or her more a performer to the congregation than a representative of them. Some think it necessary to "channel Jesus" at this point, presenting the words of institution with lots of mawkish eye contact, as though they had momentarily been cast as Jesus at Oberammergau. This is really a highly retrograde sort of clericalism, however much clad in modern vestments - for the priest's job at this point is not to "be Jesus" to the people, but to represent us all in the great act of thanks and praise.

The upshot of the change for church architecture has rarely been given much thought either. If the priest actually faces West at the Great Thanksgiving, the orientation of the Church itself to the East or otherwise is at best irrelevant at that point; it may still be significant for some other purposes such as daily prayer or personal devotions in the building. But if the Eucharist is celebrated in the now-common way, there is little reason to balk at the idea of orienting a church to the West (or any other direction) rather than to the East. There is more reason to wonder whether a Eucharist celebrated versus populum in a space designed for celebration ad orientem is really as good an idea as so many seem to assume. If we are actually to celebrate Christ in the midst, we need to consider how to use spaces and furnishings to affirm that reality, and to focus more on the centre rather than the East.

But, Percy wonders, would it not also be worth some bold liturgical pilgrim experimenting with something quite different? What about a return to the ancient practice of an eastward celebration, not from the distance of an apse but in the midst of the church, such as the ancient Christians knew? In populo, as well as ad orientem. Worth considering?